Grand Western Canal Boat Lifts

The first successful mechanical devices capable of raising boats vertically from one level to another using a power source other than the physical efforts of man or beast were James Green's boatlifts on the Grand Western Canal. They were first in the sense that they were commissioned as part of a commercial venture and operated successfully for the thirty-year lifespan of the tub boat canal. Earlier experimental lifts had never been fully incorporated into the day-to-day running of their host waterways for more than a few years.

This paper sets out to review the pedigree of his lifts, introduce some recent research, both historical and archaeological and briefly discuss the problems associated with their commissioning.

Historically, purpose built canals arrived late in the British Isles and that, combined with an era of inspired philosophical thought, social change and economic and political discussion often referred to as the Age of Enlightenment provided a fertile environment for publication of innovative and progressive ideas. One such contributor was Erasmus Darwin, physician and philosopher, a founder member of the Lunar Society, close friend and admirer of James Brindley and a promoter of canals. Thought was obviously being given to the problems of level change as in 1777 the first application of scientific principle to the problem appears in Erasmus Darwin's Commonplace Book where he eloquently and simply described the basic requirements of a device including balanced water filled caissons that could be used to raise boats from one level to another.1

Between 1794 and 1816 a series of experimental lifts were built to various designs using some form of displacement arrangement to reduce the power required to operate the machinery.2 One of these experiments was that of James Fussell, iron master and edge-tool maker of Mells in Somerset. His patent of January 17983 describes a mechanism in many ways similar to that described by Dr James Anderson in his Agricultural Survey of Aberdeenshire of 1794.4Anderson's proposal included counter balanced caissons and was a serious attempt at engineering Darwin's ideas. Fussell built an experimental lift at Barrow Hill along a branch of the ill-fated Dorset and Somerset Canal and a newspaper report of 13 October 1800 reported its successful operation.5 Unfortunately, as the canal was never completed the lift never had a chance to prove itself.

The author has not researched links between Darwin, Anderson and Fussell, but it seems likely that the ideas formulated were disseminated and James Green later referred to Anderson in his paper of 1838.6

It was during those 'heady' days of innovation and experimentation in canal engineering that James Green was finding his feet as an assistant engineer to John Rennie. Green worked for Rennie from 1802 to 1807 when he moved to Devon where he became County Bridge Surveyor in 1808.7 He built up a fine reputation as a civil engineer and became involved with the Devon and Cornwall canal projects which the Earls Stanhope, third and fourth, were promoting. Presumably it was during this period in the early 1800s that he assimilated the Third Lord Stanhope's ideas for tub boat canals which were formalised by Robert Fulton in his Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigations of 1796.8 Another possible link occurs between the Third Earl Stanhope and Erasmus Darwin, as both were Fellows of the Royal Society during the latter half of the Eighteenth Century. Tub boat canals proved to be an ideal solution to the difficult terrain and water supply problems experienced by canal builders in the South West Peninsular and James Green successfully used the concept for the Bude Canal, installing water powered inclined planes to change level.

Rennie's short summit level section and branch to Tiverton of the never to be completed Grand Western Canal was in use by the summer of 1814. It proved not to be as lucrative as hoped and plans for extensions to Topsham and Taunton had to be shelved. However, in 1815 the Company employed a retired naval officer by the name of John Twisden as clerk. Twisden had spent about six months with the Grand Union Canal Company 'learning the ropes' before moving to the Grand Western. He was also awarded a contract to maintain the canal and quickly gained a reputation for employing the worst and roughest characters in the district.9 His involvement in the building of the tub boat section was to be significant.

In 1827 the Bridgwater and Taunton Canal was opened and Green, who was aware of an interest in extending the Grand Western persuaded a number of the canal's subscribers in Exeter where he was by then well known to call a meeting.10 On 1 May 1829 he submitted his proposals for a 13-mile tub boat canal including two, or at the most three inclined planes to raise level 262 feet between Taunton and the Devon border. He also explained that that he could avoid the 'Ninehead' and other properties where (landowner) difficulties might be experienced.11 Eleven months later a further report appeared dated 2 March 1830 proposing a canal with seven lifts and one inclined plane. Why the proposals changed is not known but the following month it was resolved to proceed with the lift option.12

The line was divided into eight lots and 'Contracts for the Execution of Works'13 produced. The remaining documents include detailed written instructions for lots 1,2 and 3, 4 and 5 and refer to lift and other drawings included with Lot 8. Unfortunately Lots 6,7 and 8 are missing. Disputes were to be settled by the principal engineer, James Green. There is no mention of an assistant engineer, but it is likely that Twisden was involved in the construction of the canal. Work commenced in 1830 and apparently proceeded well apart from delays at Nynehead where line changes to hide the canal were negotiated with the landowner, William Sanford, of Nynehead Court. The changes resulted in an unnecessary cutting and embankment and the fine ornamental canal structures close to the Nynehead Lift.14

The Annual Report of 1832 indicated full confidence in the venture but that of 26 June 1833 hints at the first signs of trouble when mention of unspecified minor inconveniences is made. However, at this stage no blame was attached to the engineer or contractors and work on the first three lifts at Taunton, Norton and Allerford was well underway, the machinery being ready and the masonry nearly complete. Work was also advanced at the Trefusis, Nynehead, Winsbeer and Greenham sites. The next report of 30 June 1834 tells a different story, blaming the 'supineness and want of activity and foresight on the part of the contractors----' for delays but attaches no blame to the engineer. It also explains that the Company had run out of funds and owed money to the contractors!

The first formal indication of trouble with the lifts appears in the annual report of 1 July 1835 although by then the first five lifts were working and the canal open as far as Wellington. The Taunton lift was apparently working satisfactorily by January 1834, but Green was blamed for the delays incurred during commissioning because his design had not been tested and various modifications were tried before a satisfactory solution was found.15 Other sources provide a fascinating insight into the trials and tribulations of the company from 1833 onwards.

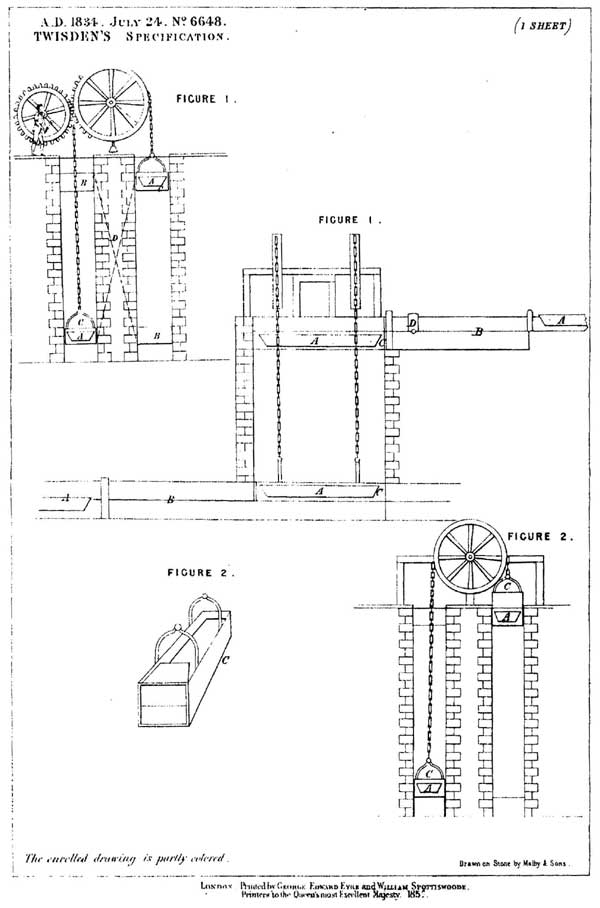

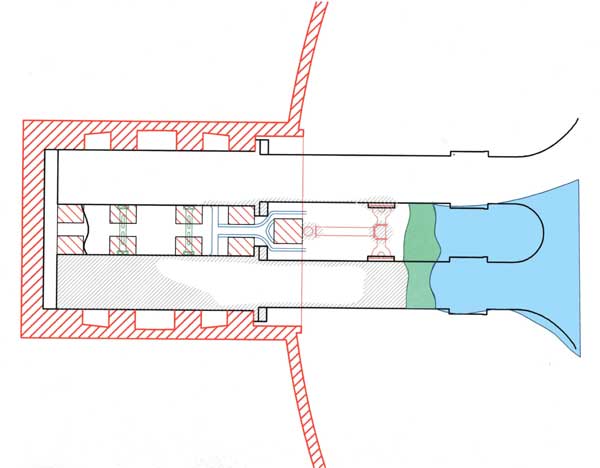

On 17 September 1834 Captain Twisden registered a patent for 'An Improved Canal Lock'.16

The accompanying drawing shows a perpendicular lift similar to Dr Anderson's, whom Twisden acknowledges, but with the addition of lock chambers at the top and bottom and a pair of cross-over pipes to transfer water from the top to the bottom chambers. The instructions for operating the system are complicated and include a description of staff ringing bells to control the operation of valves. The arrangement is extremely over engineered but a simplified version of this scheme, adding locks at the bottom only and paid for by Green was used to solve the problem. Twisden was obviously much aggrieved by this development because a document exists itemising the components of a debt to Partridge and Brien, solicitors of Tiverton, for defending the patent against James Green.17 The proceedings rumbled on for two years between February 1835 and February 1837, the dispute never reaching the courts, and ending with Twisden paying Green's expenses of £145-5s-9d. A number of affidavits were obtained including scientific ones from James Walker, William Cubitt and John Thomas (all members of the Institution of Civil Engineers as was Green) and others from Isaac Whitewood, an experienced canal engineer, and two local men, John Burridge the Elder and his son John Burridge the Younger. Unfortunately the contents of the affidavits are not known.

By the end of 1835 a satisfactory lift design was in place but there were other major problems. On 3 February 1836 the local press reported that "Mr James Green has ceased to be Engineer to this Company"18 and there is rough entry in a small accounts notebook recording that he was dismissed on 27 January,19 probably because of the continuing problems with the inclined plane at Wellisford.

The Company was in serious trouble. It appointed Twisden as superintendent and the engineer W.A. Provis was called in to report on the state of the works. His report, dated 28 June 1836,20 provides much information about the construction of the canal and the lifts which is also précised in Helen Harris's book.21 Provis was informed that the original design, which included flooded caisson chambers without gates to isolate them from the canal, intended to use machinery of sufficient power to force the descending caisson to its proper position in lieu of Dr Anderson' drained chambers. The elevation of the Taunton Lift was not much above the level of the flood prone River Tone, the only convenient place to drain the caisson chambers to, and Green was surely aware of that. Whether the system was abandoned or just not tried is not known, but the report goes on to say that gates were then fitted and pipes laid to drain the water away. That solution also failed to work. The shallow locks of 3 feet rise eventually used were probably the best solution at the Taunton site. An engine driven pump would have served but to keep a steam plant on stand-by ready for occasional use would have been an uneconomical option, as coal would have had to be imported. The first three lifts were of the same pattern and, according to Provis; the locks were added to the almost complete structures after the problems had become apparent. The caisson gates dropped down onto the caisson bottom and both lock gates moved horizontally on pivots. Green designed the canal for tub boats 26 feet 6 inches long, 6 feet 6 inches wide, 2 foot 3 inch draft and 8-ton capacity. Archaeological excavations at Nynehead confirm its caisson chambers to be 30 feet long, which is long enough to accommodate a 26 foot 6 inch boat in a caisson fitted with guillotine gates but not in one with drop down gates. However, byelaws authorised in 1838 specify a maximum boat length of 25 feet and width 6 feet 3 inches.22 Boats this size would have fitted in a drop down gate caisson. Nynehead belongs to the second group of three lifts, supposedly built with the locks, but that will be discussed later.

The land rises gently from Taunton westwards towards Bradford-on-Tone and none of the first three lifts at Taunton, Norton and Alleford are much above the present river level, but the river was probably lower when the canal was built. A question arises as to how much thought Green had given to dispensing with Dr Anderson's caisson chamber drains when the final levels for cutting the canal were determined. The next three lifts included locks but they probably would have worked with caisson chamber drains as the ground was rising at a greater rate giving more scope for dispersal of the unwonted water. Provis states that the last lift at Greenham included chamber drains and worked with out locks so somewhere, under the tons of rubble tipped onto it in 1973,23 is the adit that drained the water away.

Although the company was trading to Wellington by at the latest June 1835 there were still serious management and operational problems. There were a number of accidents and breakages at the lifts mostly caused by unreliable staff operating the machinery incorrectly.24 The company had run out of money, the request for a loan from the Exchequer Loan Commissioners turned down and construction at the western end ceased. Eventually, on 1 February 1838, twelve proprietors, disgusted by the lack of progress, called a Special Assembly of Proprietors at Sweet's Hotel in Taunton to set about completing the venture and Isaac Cooke, one of the twelve, obtained a private loan of £20,200, from an unnamed benefactor to complete the works. The loan was subject to certain conditions including completion in twelve months and a restructure of the management set up.25 This resulted in the formation of a country committee and great improvements in the running of the canal. 'Bad eggs' were sacked, lift keepers sent on training courses at the White Ball Inn, Tiverton, and an incentive provided of one extra weeks pay (about thirteen shillings) for those who operated their lifts for twelve months without mishap. Measures were taken to improve the control of maintenance teams, stop pilfering, particularly of scrap iron from broken lift parts and the control of receipts and payments tightened.26

Eventually, by the early 1840's, with the problems of the incline solved and the Greenham lift masonry stabilised the machinery was functioning reasonably well and the canal bringing in tolls, although not enough to pay dividends because of its debts. The Annual Report of 184627 praised the skills of Henry Smith, newly appointed manager, for increasing trade and reducing maintenance costs on the lifts which were by then working well. Growing competition from the railway finally brought about the demise of the canal and in 1864 an Act for the Sale to the Bristol and Exeter Railway Company of the Undertaking of the Company of Proprietors of the Grand Western Canal and for an Abandonment of a portion of the Canal was passed.28 By 1867 the Taunton to Lowdwells section was closed, the land sold, arrangements made to maintain road crossings, the machinery removed and much of the masonry either sold or robbed.29 So ended a remarkable phase in Britain's canal age. Green's lifts were designed, built, successfully used for thirty years and then dismantled nearly ten years before the construction of the Anderton lift. There had been major advances in technology since the commissioning of the first lift on the Grand Western Canal and Anderton was able to benefit from them.

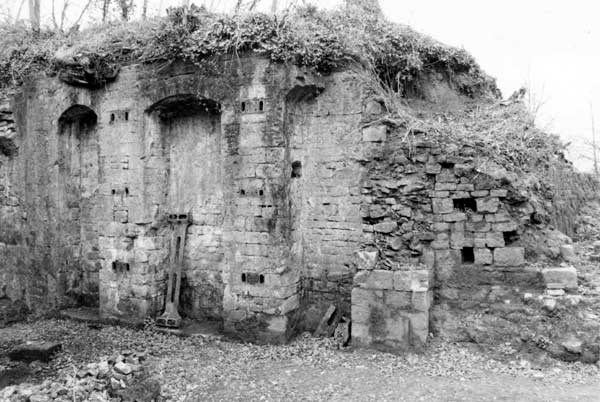

Recent limited archaeological excavation30 at Nynehead has confirmed some of the details shown on James Green's drawings of a 46-foot lift associated with his paper read to the Institution of Civil Engineers in March 1838. These drawings incorporate all the basic requirements of a tried and tested structure without the locks. Caisson chamber drains are not shown but are mentioned in the accompanying paper. The dimensions of the identifiable features exposed compare well with the side elevation and plan.

The excavations included three trial holes and a clean up of the surface of the central wall from which the upper courses had been removed. The first hole was dug at the back of the South Caisson chamber exposing a very well constructed brick invert and sockets for the timber baulks used to support the descended caisson. There is a lower one in a position that relates to Green's drawing and there is one higher up at design water level suggesting that it was added later to support the caisson after the addition of the locks.

The second was a small exploratory hole over the caisson / lock gate junction. A short length of vertical timber recessed into a groove and the wood cill were exposed. A third hole was dug at a mid-way point in the lock chamber exposing cast iron pipes used to admit water from the upper pond into the lock.

The clean up of the central wall exposed channels thought to have linked the caisson chamber to the lower pond downstream of the lock. Destruction is such that it is impossible to trace the complete course of the channels but a link would have been necessary for the system to work.

The author's opinion is that the construction of the lift at Nynehead was well underway by the time the decision to add the locks was made and that the lift was not built with the locks as Provis suggested. The lock chambers include recesses at the downstream end sized for twin mitre gates and grooves at the upstream end to accommodate the linked guillotine gates described in Provis's report. The workmanship in the lift is excellent whereas that of the locks is poor and they have rather rough finished concrete bottoms. Excavations have ceased for the time being and the site kept flooded for preservation purposes. A report is being prepared that will be deposited in the Somerset Records Office when complete and plans are in hand to protect the structure from further attack by vandals, vegetation and the elements. The North chambers remain untouched having been left intact for a future excavation.

The building of the tub boat section and its lifts is well documented and most comes from primary sources. It remains a mystery why Green, an engineer with a proven track record in the design of level changing mechanisms for canals, seemingly brought upon himself the problems associated with the commissioning of the lifts. Whether he realised the degree of force required to sink the caisson into the flooded chamber is not known, but perhaps his greatest failing was not to have conducted experiments before committing himself to a design in spite of the cost restraints and the company's desire to complete quickly. There can be no doubt that Green and Twisden were at loggerheads because of the patent and there is a suggestion that Twisden did not want Green as engineer anyway.31 That Twisden was out of his depth as an engineer is illustrated by the content of his patent and also later by his proposals for replacing the troubled incline at Wellisford.32 In those days the engineer took the final responsibility for the success or failure of a project but it is interesting to contemplate what might have been achieved if there had been a better management structure and a good working relationship between Green and Twisden.

- E Darwin, Commonplace Book: 1766-1787, 58-59

- H-J Uhlemann, Canal Lifts and Inclines of the World: 2002, Translated and Edited by Mike Clarke, 150-154

- J Fussell, Balance Lock for Raising or Lowering Boats applicable to other purposes: Patent No GB2284/1798

- Dr. J Anderson, General View of the Agriculture and Rural Economy of the County of Aberdeen with Observatios on the Means of its Improvement: 1794, 178-183

- C Hadfield, The Canals of South West England: 1967, 94

- J Green; Description of the Perpendicular Lifts for passing Boats from one Level of Canal to another, as erected on the Grand Western Canal: Transactions of the Institution of Civil Engineers, 1838, II 185-191

- B George, James Green Canal Builder and County Surveyor: 1997, 9-14

- R Fulton; A Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation: 1796

- Sir J R Twisden 12 Bart, The Family of Twysden and Twisden: 1939, 429-430

- C Hadfield, The Canals of South West England: 1967, 103

- Extract from the Report of Mr James Green, dated 28 April 1829: Exeter, Devon Records Office, DRO-74B/MB12/6

- ABSTRACT of Mr Green's Report of 2 March 1830: Exeter, Devon Records Office, DRO-74B/MB12/7

- Contract for Execution of Works, Lots 1,2 and 3, 1831 and Lots 4 and 5, 1832: Exeter, Devon Records Office, DRO-2062B/E2

- Report of the Committee to the Annual General Assembly, 27 June 1833: Kew, Public Record Office, RAIL/1019/7

- Reports of the Committee to the Annual General Assembly, 28 June 1832, 27 June 1833, 25 June 1834, 24 June 1835: Kew, Public Record Office, RAIL/1019/7

- J Twisden, Inland Navigation: Patent Number GB6648/1834

- Debt to Partridge and Brien and Agents Bill: Maidstone, Centre for Kentish Studies, CKS-U49/C9/1

- Taunton Courier: 3 February 1836

- Grand Western Canal Treasurer's Notebook 1819-1851: Tiverton, Tiverton Museum

- The Papers of Roger John Sellick, 1930-1988: Taunton, Somerset Records Office, A/BAZ7/1

- H Harris, The Grand Western Canal: 1996, 100-110

- H Harris, The Grand Western Canal: 1996, 212

- B J Murless, Notes, Journal of the Somerset Industrial Archaeological Society, No 1, 45

- Captain John Twisden, Note Books, 1802-1851: Maidstone, Centre for Kentish Studies, CKS-U49/F6/3

- Report of Special Assembly of Proprietors, 1 February 1838: Kew, Public Records Office, RAIL/1019/7

- The Papers of Captain John Twisden, 1767-1853: Maidstone, Centre for Kentish Studies, CKS-U49/C/9/7 and CKS-U49/F/3

- Report of the Committee to the Annual General Assembly, 25 June 1846: Exeter, Devon Record Office, 4508M/F32

- H Harris, The Grand Western Canal: 1996, 130-131

- Milverton High Board Minute Books 1863-1868 and 1868 1876: Taunton, Somerset Records Office D/Rwel 32/1/1 and 2

- Excavations by Somerset Industrial Archaeological Society, 1998-2003

- Sir J R Twisden 12 Bart, The Family of Twysden and Twisden: 1939, 429-430

- Isaac Cooke, Letter to Thomas Merriman, 6 February 1838: Kew, Public Records Office, RAIL/1019/7